This curve tracks the relationship between interest rates of US government debt obligations. Normally the yield curve is rising, with long-term bonds having yields higher than short-term obligations.

But occasionally the curve inverts, with long bonds yielding less than short Treasury bills – a historical predictor of future recessions and bear markets in stocks. Recently, the curve has become noticeably flatter, with short rates rising and longer yields remaining stagnant. This has led many analysts to think that the yield curve will soon invert.

But that does not mean a recession is imminent. Just returned from an extended visit back to Harvard. Touched base with my mentors and professors at both extremes of the economic spectrum. They are all split on what this flattening really means. In the event it does invert (the gap today being below 0.3%), recession has almost always (over the past 50 years) followed within a year or so. But few see a recession soon on the horizon.

The first half has come and gone. The ongoing transition to more normal conditions continue in the context of a robust US economy; continued progress in the orderly normalisation of US monetary policy; and re-awakened sensitivities to geopolitical and protectionist risks.

There will be higher interest rates, some inflation concerns and trade tariffs coming-on in the context of markets more readily accepting two to three more rate hikes by the Fed in 2018. The prospect of a global trade war makes everyone very cautious.

Once we start down the road of tariff increases and threats of more to come, the dangers of retaliatory miscalculations are real and very scary. Still even an inverted yield curve should not be on top of our worry list under today’s accommodative monetary conditions.

Synchronised pick-up

The world economy benefitted from four drivers of higher growth: the healing process in Europe, re-bound from slowdowns in Brazil, India and Russia; soft landing in China; and pro-growth measures in US.

To persist, Europe needs to do much more. Also, there is hope that recent tariff tensions would eventually lead to fairer and still-free trade which recognises the inter-dependent nature of global supply chains, and show greater willingness to protect intellectual property rights, modernize trade arrangements and reduce non-tariff barriers. Yes, more rate hikes from the Fed are still on the cards. But the same by the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) demand trickier manoeuvring.

This is an area that warrants close monitoring since volatility will likely persist. At least for now, fears of Japan-like deflation in US and Europe are effectively gone. But OECD is worried global growth is not yet self-sustaining. It’s strength in 2018 is largely due to monetary and fiscal policy support – and lacking in rising productivity gains and sweeping structural reforms. In Europe, the “clock is ticking”; without reforms, more populist uprisings will appear as the upswing ages and then fades. US inflation is not only returning to the Fed’s 2% target, but also likely to exceed it. In Europe, consumer prices were last still lower than a year ago – below the ECB’s target of just below 2%. Fear of the spectre of deflation has led BOJ to remain cautious about tapering its monetary easing program. Will just have to wait and see.

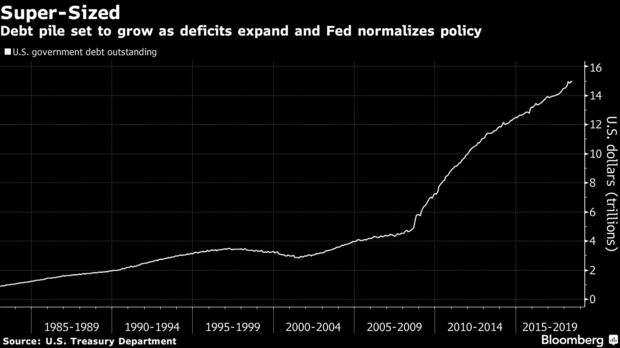

IMF warns that the world’s US$164 trillion debt pile (at 225% of GDP) is bigger than at the height of the financial crisis a decade ago. One-half was accounted for by US, Japan and China. What’s needed is for US fiscal policy to be recalibrated to bring down the government debt to GDP ratio (80%) and for China to deleverage its US$ 2.6 trillion private debt. There is no sign either is being done which runs the risk of triggering yet another financial crisis.

Growth will falter

Growth in US can slow considerably when the boosts from last year’s tax-cuts in US fades in 2019 and 2020. IMF now warns that US will grow at about one-half the 3% annual pace forecast by the White House over the next 5 years, reflecting the effects of growing massive fiscal deficit and continuing trade imbalance. For US, sluggish productivity remains a key determinant. In 2Q18, GDP picked-up to rise 4.1% (2.2% in 1Q18) the fastest pace in nearly four years, reflecting broad-based momentum.

But worker productivity advanced 1.3% from a year earlier, consistent with the sluggish 1.2% average annual rate in 2007-2017, well below the better than 2% annual average since WWII. Spending by consumers, businesses and government as well as surging exports all appeared solid in 2Q18. The expansion enters its 10th year this month, building on what is already the second longest expansion on record. Faster growth which has helped to drive the unemployment rate to its lowest level in 18 years, fueled quick corporate profit growth.

Median estimates place GDP growth at 2.8% in 2018, 2.4% in 2019 and 1.8% over the long run. But everyone has growth slowing next year because of falling business and consumer sentiment, reflecting trade disputes with China and many US allies, and uncertainty whether rising business investment is sustainable.

The big concern is the economy overheating – already, it is bumping up against capacity constraints as labour markets tighten. Still, the consensus is that the next downturn will not arrive until 2020. Most economists expect 3% inflation over the next year. What worries me most is the deteriorating global political and strategic environment.

Not so much the economic outlook directly. The world is changing too much, too fast.

So much so, the geopolitical situation is getting worse – open warfare between Israel and Iran, the disgraceful state of Palestine, and uncertainties surrounding Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, and lack of leadership in Europe. Trade barriers are causing much anxiety. It is as though what’s put in place since WWII isn’t worth a damn anymore.

Europe and Japan

Latest indications from the Brookings-FT Index for Global Economic Recovery (Tiger) show global growth has peaked and momentum has started to fade. Indeed, financial markets are already reflecting mounting vulnerabilities. With weak economic data in 1H’18, Europe and Japan have since cooled. In late 2017, eurozone was still growing at 3.5%: Germany at 4%, France 3%, Italy 2% and Spain 3.5%. But activity slackened to only 1.2% in early April; even Germany recorded a sharp dip – down to only 1%, reflecting waning monetary easing effects and supply-side constraints. The outlook is for a strong above trend upswing for the rest of the year. OECD now expects GDP growth in 2018 to be 2.2% (2.6% in 2017) and in 2019, 2.1%.

For eurozone, the window for reforms is closing – ranging from the implementation of dual currencies for its members to putting European Parliament in charge of economic policy, including the euro-budget. Japanese GDP shrank 0.1% in 1Q18 despite a rise in capital investment. Household spending unexpectedly fell. Still, recovery is expected to be driven by a weak yen brought about by monetary stimulus (BoJ has been buying assets at US$740 billion a year to drive down long-term interest rates). But underlying inflation is stuck at 0.5%. BoJ’s goal remains at keeping real interest rates (after inflation) as negative as possible, as long as the economy performs. OECD forecasts growth in Japan to be 1.2% in 2018 (1.7% in 2017); the same in 2019.

China and BRICS

Many emerging markets (EMs) are still enjoying momentum from 2017, but there is growing concern about rising debt and vulnerabilities to capital flight as interest rates in US rise. For those recently emerged from recession, viz. Russia, Brazil and South Africa, their urge to return to strong levels of activity remains sluggish.

China and India have fewer concerns for their immediate outlook. Still, they need to reform their economies to help raise living standards to catch up. The main challenges will be to execute particular reforms – not just to the financial system but also to SOEs and local governments, including getting rid of corruption.

China’s GDP rose 6.7% in 2Q’18, the slowest pace since 2016. Retail sales held up rather well as did exports. Still, measures to curb rampant borrowing are biting – investments in infrastructure and manufacturing by SOEs and local governments have since slackened. These efforts, in the midst of headwinds from abroad (especially protectionist tariffs), have led to downgrades in growth for the rest of the year. IMF now forecasts GDP growth in China to average 6.5% in 2018 (6.8% in 2017) and about the same in 2019.

Recent depreciation of China’s currency, the yuan, exposes crucial vulnerabilities within the world’s second-largest economy as it faces escalating trade tensions with the US. The currency posted its biggest ever monthly fall against US$ in June (3.4%) and has since lost more ground. This slide marks a departure for the currency often regarded as an anchor of stability for Asia and other EMs.

As Beijing assesses the options, it finds itself between a rock and a hard place because (i) People’s Bank of China (PBoC) intervention means selling its US dollar stash of reserves – which stood at US$3.11 trillion in June; (ii) it could instead raise domestic interest rates, thereby making the currency more attractive which might help to shore up the yuan. But it also risks weakening an already slowing Chinese economy just as the trans-Pacific trade war starts to bite; and (iii) it could impose stricter controls on China’s capital account which will likely spook overseas funds that have rushed into China’s domestic bond and equity markets this year at an unprecedented rate.

However, to internationalise the yuan, China has to keep fund flows relatively unencumbered. The PBoC has sensibly pledged to keep the RMB “generally stable.” In July, China implemented a mix of tax cuts and greater infrastructure spending citing growing uncertainties, as it ramps up efforts to stimulate demand to counteract a weakening economy.

As for India, I wrote extensively on what’s happening there (my July 2018 column: “India: Chugging Along but Needs More Firepower” refers).

What then are we to do

As I see it, China and China-India centred Asia is now the heart of the world economy. Their steady growth has been a source of stability in an otherwise unsteady world.

Of late, developments in China received more scrutiny than usual because of the context: Chinese stock market has since fallen into bear territory, and a growing trade dispute with the world’s largest economy, US. Despite China’s astonishingly sustained expansion, the economy is widely considered vulnerable because growth in output has been underwritten by an even faster increase in debt.

The nation’s gross debt – both public and private – is now estimated at over 250% of GDP. The worry is not just the volume of debt but its quality. China’s domestic policies encourage high savings.

Those savings, held in banks, have been funneled to companies, especially SOEs. The credit quality of the loans is hard to assess but is likely to be uneven. China has since begun to slowly tighten the credit taps, with even tighter rules on shadow banking and more scrutiny for both local government financing and public-private investment projects.

At the same time, a sharp increase in the number of defaults by corporate issuers has revived anxieties about Chinese debt. In my view, it is the tighter credit conditions and defaults, rather than worries about a trade war, that best explain the recent 22% decline in the Shanghai Composite index from its January highs.

Tightening credit policy is also a compelling explanation for the weak macro-economics. Credit growth fell, and growth in fixed investment followed. This appears to be having some effect on consumer sentiment as well.

No doubt, Trump’s tariffs on US$50bil of Chinese imports (and threatens US$200bil more) will have a direct (but unlikely to be catastrophic) impact on growth. But China is now an investment-led rather than an export-led economy.

Still, it is the knock-on effects that are most feared. If the escalation of hostilities leads to a reduction in foreign direct investment in China, the long-term impact could be significant. True, China may be facing a delicate moment economically.

But given China’s deepening role in the world economy, any pain that the US manages to inflict on it would be quickly shared with the US and the broader world – at a moment when Europe’s economy is slowing, and many EMs looking unstable.

On the whole, China’s economy will remain strong and resilient. Whatever happens, I think this won’t change the Chinese situation much.

By Lin See-yan - what are we to do?

Former banker Tan Sri Lin See-Yan is the author of The Global Economy in Turbulent Times (Wiley, 2015) and Turbulence in Trying Times (Pearson, 2017). Feedback is most welcome.

Related news:

Related posts:

Recalling Bank Negara’s massive forex losses in 1990s

Global economic order under threat

Bizarre world of new debt, low, even negative interest rates a threat to global stability

Bitcoin: Utter pipedream

Global economic order under threat

Coming global economic crash, threat of WWIII, petitioned 2030 Agenda

for a One World Global Government under a New World Order. http://jimdukeperspective.com/1526-globalagend/

Related:

No comments:

Post a Comment