|

| Bureaucratic staying power: While boy band BTS may be going places (no, that Grammy award is not theirs), a government survey shows that one in four middle-school students in South Korea dream of one day becoming not K-pop star or the next Steve Jobs, but that 'adjussi' in the civil service - Reuters |

|

Desire for stability: Many South Koreans worry

far more about jobs and the economy than they do about the nuclear

threat from North Korea, like this jobseeker at a jobs fair in Seoul

last November. — AFP

|

|

| South Korean Finance Minister Hong Nam-ki, third from left, makes

remarks at a meeting on reviving the economy at the government complex

in Seoul on Jan. 9, 2019. (YONHAP / EPA-EFE/REX) |

In a tough market, young South Koreans dream for the security of government jobs instead of tech innovation and K-pop success.

For more than three years, Kim Ju-hee has been studying full time for an exam that feels like her only shot at a good life in South Korea.

She’s lost count of how many times she’s taken the nation’s civil service exam and failed — though she knows it’s been at least 10. The 26-year-old is not sure what she’ll do if she fails again, so she figures that spending more than eight hours a day studying for her next try, on April 6, makes sense.

Kim hopes to become a government tax clerk, which offers a starting salary of about $17,000, and work for the government until retirement.

“There just aren’t other good jobs,” she said in a phone interview from her home in Seoul, where she lives with her parents.

The most sought-after careers among teenagers and young adults in South Korea, Asia’s fourth-largest economy, are government jobs they can count on to get them to their golden years, not jobs innovating and helping companies grow in the private sector.

Analysts say it’s a symptom of the nation’s slowing economic growth and competition from China in export-driven industries that young South Koreans, about a fifth of the 51 million population, are flocking to what they consider risk-free government jobs not vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the economy. The situation is particularly concerning because it was private companies in sectors like electronics, autos and shipbuilding that fueled South Korea’s rapid growth from one of the world’s poorest nations in the 1960s into an economic powerhouse, analysts say.

Many young people in South Korea say they don’t expect nongovernment job prospects to improve anytime soon despite a host of measures announced by South Korean President Moon Jae-in nearly a year ago to boost employment, including government stipends to companies.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in, right, puts on a safety helmet during his

tour of a hydrogen plant in Ulsan, South Korea. Critics have pointed to

the lackluster economy to say the president should be focusing on

bettering South Korean lives, engaging with North Korea. (YONHAP /

EPA-EFE / REX)

Unemployment among those ages 15 to 29 reached 11.6% last spring — a level Moon called catastrophic, compared with a jobless rate that hovered between 3% and 4% for the rest of the country’s workforce. Taking into account young adults who are working part-time jobs or studying for an employment exam like Kim, nearly 1 in 4 are out of a job. By comparison, in the U.S., unemployment among those ages 15 to 24 fluctuated between 8% and 9% in 2018. South Korea uses a different age bracket to calculate its youth unemployment because of mandatory two-year military service.

The desire for stability and security starts so young that 1 in 4 middle school students say they dream of one day becoming not a K-pop star or the next Steve Jobs, but a public sector bureaucrat, according to a government survey from 2017.

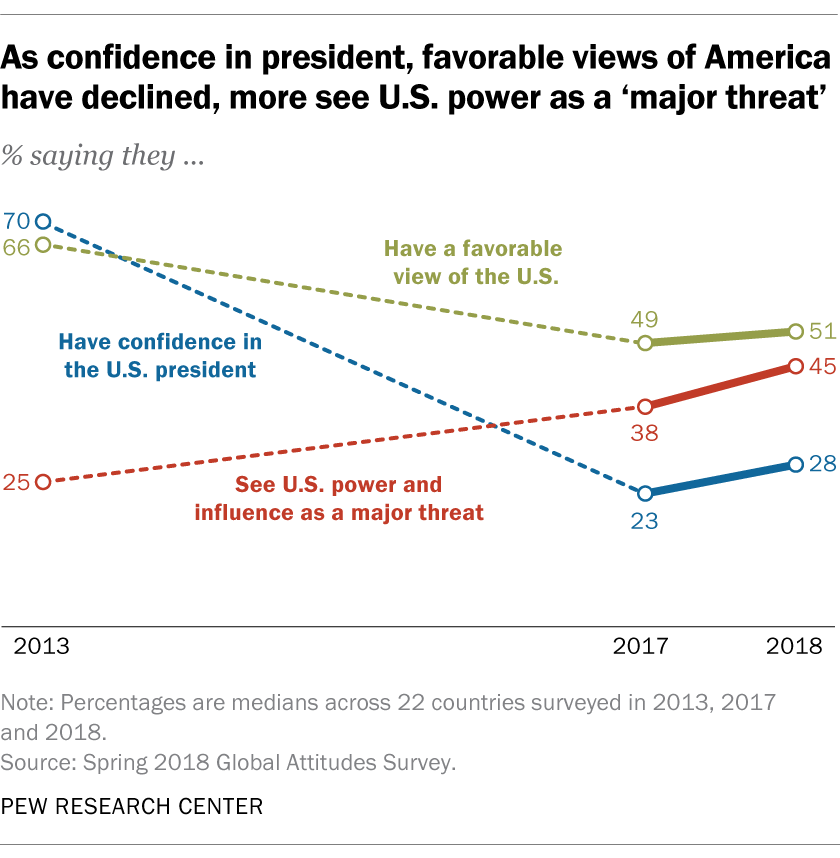

Many South Koreans worry far more about jobs and the economy than they do about the nuclear threat from North Korea. Conservatives in South Korea who are critical of Moon’s efforts at detente with North Korea point to the economy, saying his focus should be on bettering lives in South Korea, not on engaging with the North.

Competition for South Korea’s 1.07 million government jobs is fierce. In one round of exams Kim took last year, more than 200,000 people applied, and the 4,953 highest-scoring candidates were hired for open positions — an acceptance rate of 2.4%. By comparison, Harvard’s 2018 acceptance rate was 4.59%.

Kim Y.H., 22, who is about to graduate from college in February with a degree in Japanese, recently began studying for a civil service exam to become a customs agent. She said the popularity of public sector jobs was a sign that her generation is pessimistic about South Korea’s economic outlook.

“The country won’t guarantee your future, even if you’re a college graduate,” she said. “So of course we want to go with the most stable path that’s out there.”

There isn’t the expectation that you’ll grow or get good treatment in the private sector. People choose stability over risk or challenge.

Joo Won, economist

Share quote & link

One research report published last year estimated that as many as half a million South Koreans were studying for civil service exams full time instead of working. In 2017, the Hyundai Research Institute estimated that the economic cost from the lost work potential of so many young people spending years studying to get government jobs, rather than joining the private workforce, was more than $15 billion.

Moon’s administration has tried to encourage employment among young adults by paying small and medium-sized businesses to hire them, and by offering government-matched savings programs for young workers. He has also pledged to add 174,000 government jobs by 2022 to meet the heightened demand.

Some analysts, however, say the administration’s stopgap measures won’t do much to fix the problems underlying the push for government jobs.

“There isn’t the expectation that you’ll grow or get good treatment in the private sector. People choose stability over risk or challenge,” said Joo Won, one of the authors of the Hyundai study. “There are only so many public sector jobs the government can create. It won’t fix the situation.”

Many analysts point to the widening gap between the behemoth family-owned conglomerates that dominate the South Korean economy, such as Samsung and LG, and other companies. Large corporations including the chaebol, as they are known, accounted for about half of the revenue in South Korea in 2017 but provided only 20% of the jobs in the country, according to the most recent figures available from the government. And while their share of the economy grew, the number of jobs they offered dropped, because of consolidation and downsizing within the corporations amid the economic slowdown.

A Samsung flag and South Korean flag outside the Samsung building in Seoul in January. Analysts say part of problem for young job seekers in South Korea is the widening gap between the quality of jobs at family-owned conglomerates like Samsung and the rest of the players. (Jung Yeon-je / AFP/Getty Images)

A Samsung flag and South Korean flag outside the Samsung building in Seoul in January. Analysts say part of problem for young job seekers in South Korea is the widening gap between the quality of jobs at family-owned conglomerates like Samsung and the rest of the players. (Jung Yeon-je / AFP/Getty Images)

That polarisation means stark disparity in

income and working conditions between those employed by the

conglomerates and those employed elsewhere – with starting salaries at

large corporations averaging about US$36,000 (RM 146,370), compared with

approximately US$24,000 (RM97,580) at smaller companies – fuelling

intense competition for a decreasing number of coveted jobs.

“The world was harsher than I thought,” she said.

“If you work for a small or medium-sized company, you become a second-class citizen” with a fraction of the income, long hours and poor benefits, said Kwon Soon-won, a business professor at Sookmyung University in Seoul.

Those without the impressive resumes increasingly needed for jobs at the top companies — internships, perfect grades, proficiency in a foreign language or three — are turning to civil service exams.

Applicants to civil service exams tripled from 1995 to 2016, according to a report by the Seoul Youth Guarantee Center. One online bookseller said it saw a 73.5% increase in sales of civil service exam prep books in 2016 compared with the previous year.

Kwon said South Korea’s high education level is part of the problem — although 70% of those ages 24 to 35 have college degrees, the economy hasn’t kept pace by creating enough quality jobs to meet the increased expectations of those graduates.

Kim Eun-ji, 26, certainly feels that way. With an economics degree from Chung-Ang University, a top-10 college in Seoul, she applied to more than 50 jobs at a wide range of companies big and small but never got past first-round interviews.

“If I think about how many people there are like me in the country, it just feels pointless,” she said, leaving an employment center in Seoul.

She has been studying for a government-issued computerized accounting license to better her employment prospects. Among her friends who graduated around the same time she did in early 2016, only about half are employed full time, Kim said.

Her roommate, who keeps deferring her college graduation, has been making a modest but steady income publishing romance novels online, which strikes her as a more viable option at a steady income than traditional employment.

As a kid, Kim Ju-hee had dreamed of becoming a singer or a teacher. But as an eighth-grader, hearing how hard it was to get a stable job, she set her sights on becoming a bureaucrat.

She’s gotten close to giving up, occasionally applying to other jobs or working part time here and there. But she worries that if she gives up, she’ll have spent years of her life in vain because none of what she studied for the exam will be useful for other jobs.

Victoria

Kim reports from Seoul, South Korea, for the Los Angeles Times. Since

joining the paper in 2007, she has covered the state and federal courts

and the Korean community in Los Angeles. Her work has included

investigations on the cover-up of the sex abuse scandal in the Los

Angeles Archdiocese, killing of unarmed suspects by the Inglewood

police, underpaid workers in the garment district and unaccredited law

schools in California. She has previously written for the Associated

Press in South Korea and West Africa, as well as the Financial Times in

New York. Victoria was raised in Seoul and graduated from Harvard

University.

Related posts: